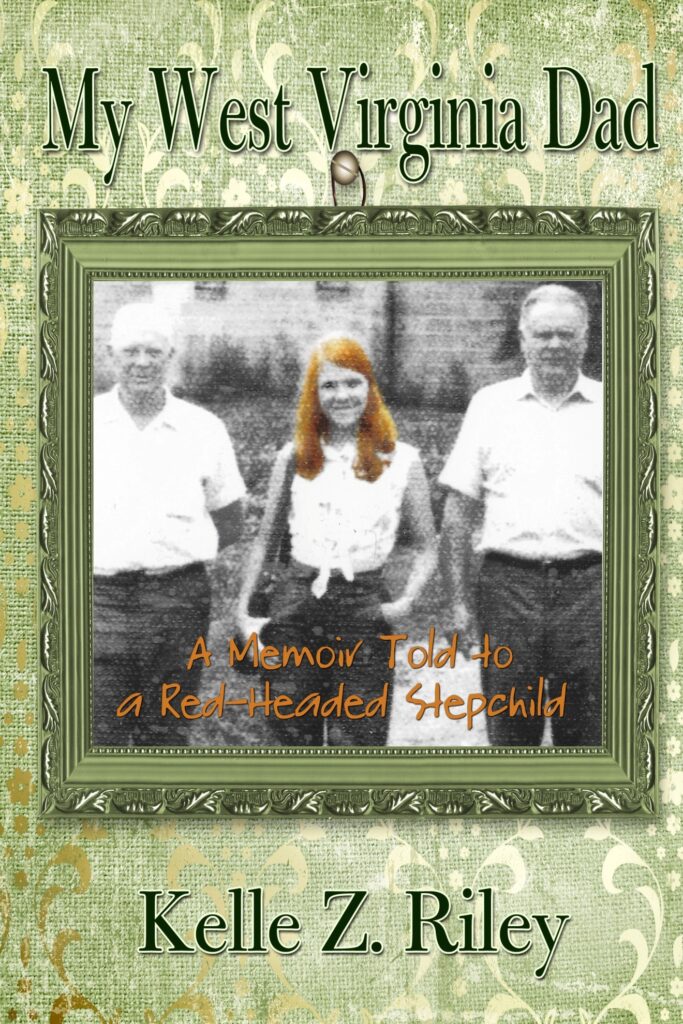

My father knew that times were difficult in West Virginia. He took me aside one day and told me that I needed to go to Ohio. “Son,” he said, digging into his pockets and pulling out a handful of change, “this is all the money I have to give you. Take it for your trip. Here’s what you’ll need to do. You’ll have to swim the Ohio River. Once you get across, take this money to the first store you see and tell the proprietor that you want it all in cheese and crackers. It’ll be enough to hold you over until you can get a job.” And he sent me off. So I did as he told me. I hopped into the river and started to swim. Every time I got near the half-way point, a barge would pass me by and the wake from the barge would push me back toward the banks of the river. But I kept going. Finally, exhausted and near the end of my strength, I made it to the Ohio side of the river. I pulled myself out and staggered to the nearest store, following my father’s advice. I put my money on the counter and asked for it all in cheese and crackers. The owner looked at me quietly for a minute, then said, “Son, you’re from West Virginia, aren’t you?” “How did you know,” I asked, wondering if my looks, or perhaps my still-damp clothing gave me away. “Well, you see, you’re the third one I’ve had this week asking for cheese and crackers. Son, I have to tell you—this here’s a hardware store.” —Howard H. Bennett

Spring 1950, Columbus, Ohio

Despite the years of hardship, despite struggles with money, health, and a host of other things, Howard “Snortin’ Horton” Bennett maintained a keen sense of humor. But his fictional struggles with the Ohio River were symbolic of the struggles he faced in the early days away from all that was familiar. From all that was home. He took an old six-cylinder Chevrolet, borrowed $20 from a friend to buy a tank of gasoline and supplies and drove all day Sunday and through the night to reach Columbus, Ohio. The first night he slept in his car. The next morning, he presented himself to the Union Hall of the Ohio Operating Engineers and applied for a job. Somehow, whether as an apprentice, a probationary member, or a member pending approval, he was accepted. Then he went in search of a place to live. He found a sleeping room on the 3rd floor of a rundown apartment building on 11th Avenue in Columbus. The room was furnished with an old, creaky bed covered by a thin, stained mattress and little else. The bed stank of urine from the children who’d slept in it previously, but at least the bleak room was warm and out of the weather. Best of all, it only cost $6 each week. During those first weeks he began a job with Bennington Company, doing common labor on the job site. Often, the laborers were sent home if there wasn’t enough work to justify having them on-site. One day while on a bridge job, a group of laborers were dismissed due to foul weather. As Howard left the site, he saw an operator sitting in a crane, not making any attempt to leave. When he mentioned it to a supervisor, he learned crane operators were guaranteed a 40-hour work week, rain or shine. He left the job site and stopped off for some dinner before heading home. In those days, when paychecks were slim and money tight, his evening ritual was to stop at the White Castle hamburger joint where he could buy two White Castle burgers and an orange drink for a quarter. As he washed the burgers down with the last of his drink, thoughts whirled in his head. If he continued to work as a laborer, taking the meager hours the job offered, he’d never get out of the cramped, stinking room where he lived. He’d never eat his fill or be able to afford more than two tiny burgers for supper. And most of all, he’d never be able to help his family if they needed him in the future. But there was a way out. He’d become a crane operator.